First Issue of Distilling Frenzy

On "China's Tech Twitter", Apple Podcast and Regulations

Housekeeping

Welcome to the first issue of Distilling Frenzy!

If I am not wrong, most of you receiving this email should have subscribed via the Distilling Frenzy website.[1] For those who did not and are forwarded this from a friend, I would recommend checking out the this page for a preview of the themes to come. Previous writings that are particularly representative are:

This essay series on Apple’s strategy in China (long but parts are largely distinct).

This shorter write-up on recommendations for TikTok’s political ad strategy.

Going forward, I will try to ensure the content between the newsletter and the website is consistent, the website’s version should be taken as canonical.

Thank you for subscribing! Feedback welcome :)

即刻 is Back

This was originally a Tweet that I subsequently turned into a post. 即刻—to date, it does not appear to have an official English name, ad thus will be transliterated as JiKe—is the closest Chinese analog to tech Twitter, filled with hot takes by Chinese VCs and PMs. It is now back in the App Store after having been removed for running foul of Chinese laws.

While it was blocked, it was reincarnated as Jellow and was distributed using Apple Developer Enterprise Program, bypassing the gatekeeping role of Apple’s App Store. Now that the original app is restored, Jellow has since been deprecated.

Based on this widely disseminated LatePost article, JiKe was taken down in the first place because of content moderation issues.

This episode provides a neat glimpse into the mechanics of Chinese Internet regulation. For those looking to arbitrage insights across Western and Chinese Internet tech, using 即刻 is probably a good choice. Throughout the article, the exact issue was never really spelled out. It noted that before the ban, JiKe relied mostly on algorithmic content moderation but has now built up a team of 100+ people in Ningbo.

Notably, in this new version of the app, users can no longer private message each other. (The causality here is unclear.) Anecdotally, I've been told that there are emerging guidelines (?) and best practices on how the back-end of Chinese social media content moderation systems should be designed, but I don't know enough to have a view on this. If this is right, it illustrates the regressive effect of regulation in general. To wit, WeChat's network-effects-style natural monopoly is certainly further enhanced by the regulatory barrier imposed by Chinese content moderation.

Despite its ban and other competitors seeking to fill its niche (e.g. ByteDance's 飞聊), none has clearly emerged to replace it. (To reduce it to "China's Tech Twitter" is probably unjust. It is also Reddit-like in the way it organizes content by community more explicitly than Twitter's more "free-for-all" style.)

For those interested in the mechanics of Chinese regulation, it is also worth noting that user generated content and data were not lost through this ban (i.e. there is continuity of content in the off-App-Store reincarnation Jellow and now in the restored app).

Jike is also not shy about the fact that it had been blocked. Users re-joining the app (like myself) were shown a welcome video that briefly analogized the ban to "an unexpected snowstorm".

Using JiKe as an information source is likely to pay off for those interested in arbitraging across Western and Chinese tech trends.

Apple Podcasts and China

In my previous essay series, I have variously mentioned that:

Apple's services are either banned (iBooks, iTunes Movies) or poorly in China (Apple Music, iMessage, Apple Pay);

The iOS App Store has removed apps that violate Chinese laws and regulations;

Apple has forbidden the engraving of sensitive terms in China and restricted the input and display of the the display and input of the flag of Republic of China (🇹🇼) in iOS 13.1.1.

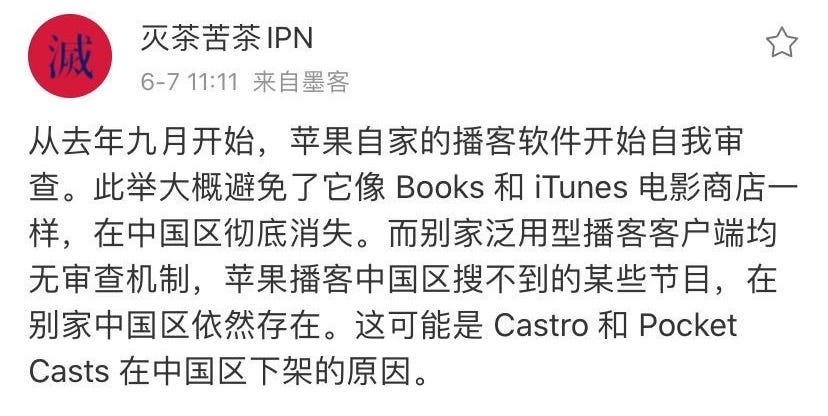

However, I have omitted to mention Apple Podcast, which has recently implemented self-censorship in China. According to the Weibo post below, Apple's self-censorship has begun in earnest since September 2019 and certain podcasts can no longer be found using the Apple Podcast app.((It does mention that these (unnamed) podcasts can still be found using other "general podcast apps" without censorship. Apple obviously has much more to lose compared to these companies and thus greater interest to implement content moderation.)) This might be why other podcast apps (e.g. Castro and Pocket Casts) have also been removed from the Chinese App Store.

Speculatively, as the podcast space is starting to take off, regulators in China are starting to pay attention to this space.

This is another illustration of Apple's no-win service strategy in China.

On the one hand, it needs wider adoption of its services within China to enhance its operating system-level lock-in. Yet, as a hardware manufacturer at its core, Apple is organizationally ill-equipped to develop compelling services that succeed on their own merits, even in the West, rather than relying on the distribution advantage of being bundled with the iPhone.((No one quite knows what Apple hopes to achieve through its spending on original content for Apple TV+, for instance.))

On the other hand, services are also especially cumbersome in China, where domestic competition is intense and the burden of content moderation is high. Regarding the latter, I refer not just to the actual, administrative cost of removing content, but also the reputational risk such removal will have for Apple in the West.

This is most starkly illustrated in podcasts, a category that Apple has pretty much created single-handedly with the iPod (that's where the "pod" in "podcasts" comes from) but has since shown no interest of capitalizing upon, despite its announced shift in strategy to services.

This is probably what Peter Drucker meant when he said, "“Culture eats strategy for breakfast.”

In the Pipeline

Two pieces of recent tech news that are thematically similar to the two items above:

Zoom’s decision to shut down a meeting with Chinese attendees (my Twitter hot take);

Twitter’s vs Facebook’s divergent treatment of Trump’s messages.

If we look past tech, it is clear that standards of acceptable content and speech are evolving the world, a change arguably catalyzed by social media.

From NYTimes: A statue of Winston Churchill was covered to protect it from vandalism in Parliament Square in central London on Friday.

We are 10+ years into the advent of smartphones and are now witnessing the consequences of two truisms: (1) software is eating the world; and (2) you are what you eat. To quote Matt Levine:

“Everything you hate about The Internet is actually everything you hate about people,” says Balk’s First Law, the clearest example of this sort of thing: The internet is a structuring and indexing and reflection of the world, and so if the world contains horror and misery and evil and ignorance then so will the internet.

Tech has grown as fast as it has because it has been a relatively unregulated part of the economy and it has largely gotten away with providing one standard product to the whole world.

I predict that, in 2020s, this will change. Regulations will start to catch up with innovation, but often with unanticipated consequences. (There probably isn’t an actual person in Brussels who thinks clicking [I Accept] on every website you visit is a universal expression of your inalienable right as a human being.) Expect lower margins and less dynamism. A still open question is whether the Internet will undergo greater fragmentation, or be dominated by the lowest common denominator.

I intend to focus my reading and writing in this general direction.

In the pipeline, I am researching on the Chinese government’s decision in 2018 to prohibit CallKit in iOS and looking into how WeChat has actually fragmented into two products—one for Chinese users and when for non-Chinese users. Will this be the fate of Zoom?

If you know others who are interested in such themes and topics, please forward this newsletter along!

Thanks for reading and feel free to reply to this email if you have any tips/suggestions.

[1] If you don’t remember signing up, it is likely because you were a subscriber of my previous Substack, Convexity. I am now re-booting my attempt to write online, except this time with the website as the mainstay, rather than the newsletter. Please feel free to unsubscribe if this content is not to your liking.