Distilling Frenzy #4: Apple's "Inspiration" for App Clip and the Future of Native Apps

If good artists copy and great artists steal, Apple is certainly a great artist.

Overview

Smartphones have emerged as and likely will remain the most important computing platform for the foreseeable future. Mini-apps, as an emerging paradigm of mobile computing, is a space worth watching.

WeChat’s Mini-Programs has proved the success of mini-apps and have inspired a host of imitators.Unlike other imitators, Apple’s App Clip has come closest to capturing the underlying philosophy of WeChat’s Mini-Programs: tool-first, “easy come, easy go”, online-to-offline (O2O) integration.

The success of any given company’s attempt to implement mini-apps depends on the degree of “product-company fit”. Tencent and Alibaba have found such a fit, whereas other imitators thus far have not. Will Apple?

Apple’s App Clip is likely to be differentiated on the basis of software-hardware integration, whose impact on the mini-app user experience remains to be seen.

Extrapolating current technological trends, the possibilities enabled by mini-apps will enlarge in the future. This will reduce the role of native apps and is a threat to Apple’s toll-bridge App Store business model.

App Clip is best understood as a defensive measure to forestall in the rest of the world the rise of other WeChat-like cross-platform Mini-Programs that further empower themselves at the expense of iOS as a platform.

If good artists copy and great artists steal, Apple is certainly a great artist.

During the recent online-only WWDC, Apple's App Clip announcement prompted me to Tweet about how App Clip drew inspiration from WeChat’s Mini-Program:

I noted that App Clip is similar to WeChat’s Mini-Program in (1) using QR code for discovery and (2) integrating its own identity and digital payment services. (Left is Apple’s “visually beautiful and distinct” App Clip. Right is WeChat’s Mini-Program QR code.)

I further predicted that App Clip—as an iOS-exclusive feature—is unlikely to fare well in China against cross-platform Mini-Program by Chinese BigTechCos unless there are App Clip-only APIs that enables a significantly differentiated user experience.

Upon further research, I discovered that Apple is only the latest in a long line of WeChat’s Mini-Programs imitators. But Apple’s App Clip has come closest to capturing the underlying philosophy of Mini-Programs. These imitators are:

Other Mini-Programs: after WeChat proved the viability of Mini-Programs, other Chinese technology companies followed quickly. Of these, only Alipay has achieved a success of comparable scale.

Google Play Instant: Google has previously rolled out the conceptually similar Android Instant Apps back in May 2017, which has since been re-branded as Google Play Instant. Its lack of mindshare (in contrast to, say, WeChat’s Mini-Program) speaks to the extent of its success.

Quick App (快应用): the Android-only, China-only alternative to Google Play Instant and Mini Programs formed by a consortium of Chinese smartphone manufacturers in March 2018. The provenance of Quick App should be enough to raise eyebrows.

In this essay, I will provide an overview on these "mini-apps", the term I’ve coined to refer collectively to these various bite-sized offerings that complement and compete with native apps.

I will begin with WeChat’s Mini-Program, before briefly discussing Alipay and other imitators. I will then discuss Quick App, Google’s Google Play Instant and Apple’s App Clip. Finally, I will conclude with some speculations on the future of native apps.

Before we begin, a clarification on geographic availability: Mini-Program and Quick App are—so far anyway—a China-only phenomenon, whereas Google Play Instant, along with the rest of Google Mobile Services, is blocked in China. Apple’s App Clip—as with Apple’s software generally—is the only one that is globally available.

For a table comparing Mini-Program vs Quick App vs App Clip from a developer-centric perspective, click here (translated with permission from @janlay; original here).

Mini-Program

WeChat’s Mini-Program is the pioneer that proved the viability of the mini-app model. WeChat founder Allen Zhang officially launched Mini-Program in January 2017.

To understand Mini-Program, we must first understand WeChat. On Eugene Wei’s three axes of dissecting social networks—social capital, entertainment and utility—WeChat absolutely dominates the last axis.[1] As Eugene Wei puts it:

While I hear of people abandoning Facebook and never looking back, I can't think of anyone in China who has just gone cold turkey on WeChat. It’s testament to how much of an embedded utility WeChat has become that to delete it would be a massive inconvenience for most citizens.

Allen Zhang has consistently emphasized that WeChat is a tool and not a platform. This is reflected in WeChat’s design choices, which prioritizes WeChat’s tool-like nature even at the expense of time spent by users:

Unlike basically every other social media feed, WeChat’s Moments feed (the News Feed equivalent) is actually sorted chronologically, not algorithmically. This avoids the highly addictive “variable rewards” feedback loop as propounded in Hooked.

Relatedly, Allen Zhang is famous for his resistance against monetizing WeChat via advertising. Today, ad load on WeChat is relatively low and ads are only displayed within Moments. This level of restraint is remarkable, and not just by Chinese standards. For example, Facebook displays ads within Facebook Messenger.

This WeChat-as-a-tool philosophy is embodied in the initial design of WeChat’s Mini-Program. As Dan Grover noted, Mini-Program was originally intended to implement a “easy come, easy go” (用完即走) vision of online-to-offline (O2O) integration.

The envisioned user flow is thus: the user encounters a QR code in real life, scans it using WeChat, launches a Mini-Program that loads instantly, completes the transaction, and closes the Mini-Program. Easy come, easy go. Social sharing was meant to be a distant second method of discovery.[2]

Of course, as Mini-Programs developed in sophistication, this user flow is complicated by features like deeper linkages to Public Accounts, quick access menu, membership functionalities and so on.

Importantly, Mini-Programs in a sense “grew out of” Public Accounts—imagine a mobile-only, accessible-by-WeChat-only Facebook Page. First, Allen Zhang observed that many companies were creating and distributing products via Public Accounts because of the lower costs of development, customer acquisition and distribution. Mini-Programs are intended to provide more functionalities while keeping these costs low. Second, Chinese users were already used to scanning (square-shaped) QR codes to access a company’s WeChat Public Account. Thus, Mini-Programs could build upon this existing habit, albeit relying on a circular QR code design for differentiation.

Compared to native apps, Mini-Programs enjoy lower costs of development and superior distribution. The file size limit puts a natural ceiling on the complexity on Mini-Programs. Furthermore, the same Mini-Program works across both iOS and Android (unlike the three other mini-apps examples discussed) on an app that is installed by effectively all Chinese users. By loading instantly and not taking up space, users’ perceived barrier to trying the Mini-Program is lower.

WeChat manages the permissions of Mini-Programs in an operating-system-like way. For example, if I have previously granted location permission to WeChat, if I open a shared bike Mini-Program for the first time, it will be WeChat and not the operating system that is asking me to grant permission (sub-permission?) to the Mini-Program.

On iOS, this is also probably a violation of Apple’s App Store policy. On this point, it should be noted that during its closed beta, Mini-Programs was originally called 应用号 (roughly, “app account”). But Apple demanded that the name be changed to “program” (程序), instead of “app”.

By all accounts, WeChat’s Mini-Program is an astounding success. According to the most recent statistics I could find, in 2019, on the back of WeChat’s 1.15 billion MAU (monthly active users), WeChat’s Mini-Program has achieved a DAU (daily active users) of 330 million. There are more than 1.5 million Mini-Program developers and more than 3 million Mini-Programs. WeChat’s Mini-Program have facilitated transactions of 1.2 trillion yuan (US$174 billion) worth of GMV (gross merchandise value) in 2019. The average user launches more than 60 Mini-Programs in a year and uses 15 minutes of Mini-Programs each day.

To put these numbers in human terms, I have used Mini-Programs to access digital menus in restaurants and to place shipment order for packages. I have used Mini-Programs to unlock shared bikes, hail car rides, place e-commerce orders, and check my email.[3] Notably, many of these use cases fall somewhere in between a native app and a webpage in terms of usage frequency and APIs required to perform the transaction. This has in turn shaped user behavior: during China’s shared bike craze, I noticed my Chinese friends were very nonchalant about downloading native apps, preferring to use WeChat’s Mini-Programs instead.

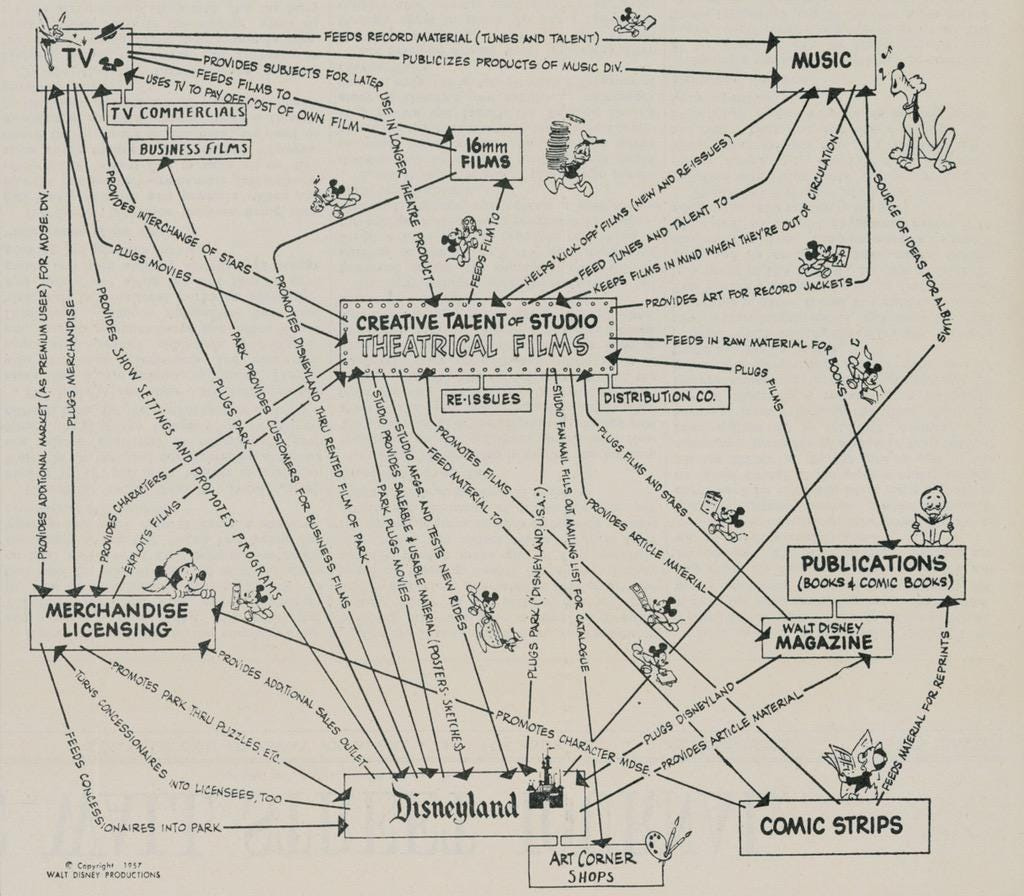

WeChat Mini-Program’s success can also be explained in terms of “product-company fit”. Mini-Program has great value-add to WeChat Pay, improves engagement of WeChat itself and has synergies with Tencent’s cloud and ad businesses. Many of these are mutually reinforcing loops a la Walt Disney’s corporate strategy in 1957.

Beyond increasing utility, Mini-Programs have also made progress on the entertainment axis. While games were prohibited when WeChat’s Mini-Program was first launched, today, Mini Games is now a genre of lightweight games that start up instantly without installation and and can be monetized via in-game purchases and advertisements. According to WeChat, already has over 2,000 Mini Games, 310 million users, and 10 million DAU.

The success of WeChat’s Mini-Program has naturally inspired imitators. Alipay’s Mini-Program was officially launched in September 2018 and has gained significant traction. According to 36kr, in 2019, on the back of Alipay’s 1 billion global users (850 million of which are in China), there are more than a million Mini-Programs with a MAU of 600 million. Unlike with WeChat, I was unable to find more detailed statistics. Personally, I have also used Alipay’s Mini-Programs with far less frequency than WeChat’s—typically when I’m trying to use Alipay to pay for the transaction so as to boost my Sesame Credit score (*cues dystopian music*). This points to Alipay’s Mini-Programs “product-company fit” as a complement to Alipay’s digital payment business.

Much like competitors to WeChat and Alipay’s duopoly in digital payments, there are a slew of other wannabes in the Mini-Programs space. Tencent itself has a second offering in QQ Light Apps.

The other wannabes include Baidu and ByteDance. I was unable to find authoritative statistics on the usage of these other Mini-Programs, except for vague claims of users numbering in in the “hundreds of millions”. In private correspondence, I was told:

Nobody really cares; to the extent they are developing for these platforms, they are developing for WeChat and then porting the apps. The APIs are so similar (since they’re all copying WeChat) and there are even frameworks to make it easy that x-compile to the different DSLs. I will, say, though, Baidu has some interesting advantages being able to open Mini Programs via search. WeChat has also tried to create that synergy, but they don’t really have search (they are trying to promote it with Sou Yi Sou). Baidu, lacking WeChat’s user numbers, has also tried to make the platform work in a whole bunch of different apps via their supposed “开源联盟”.

That these other Mini-Program attempts do not have “product-company fit” might explain why they have failed to take off in a similar way.

Quick App

In March 2018, major Chinese smartphone manufacturers—Huawei, vivo, Oppo, Xiaomi, Lenovo and so on—formed a consortium to support Quick App.

The vacuum left by Google Play’s unavailability in China has resulted in even worse Android fragmentation than in the rest of the world. Each smartphone manufacturer—in their attempt to create an Apple-like ecosystem—operates its own app stores, cloud backup services and so on. However, for Android developers, having to deal with multiple SDKs and app stores with different rules is a massive headache.

Mini-Programs are thus an alternative that can serve not only all Chinese Android users but also iOS users, whose customer lifetime values tend to be much higher than Android users. Also, note that that WeChat’s Mini-Program on Android is not constrained by Apple’s App Store rules and thus can, say, use WeChat Pay to complete transactions for digital goods and services.

Instead of further competition as with app stores, Android manufacturers instead are working together to counter the Tencent threat by providing a native alternative to Mini-Programs.

Is Quick App a success? On the one hand, I have never heard of it when I was in China. As a friend puts it privately: “Chinese phone industry has all sorts of shitty standards that no one cares about, even other Chinese tech cos”. On the other hand, a research report released in Jan 2020 boasts the following impressive statistics and achievements:

By December 2019, Quick App has a MAU of more than 300 million, compared to 200 million in March 2019.

On average, each user opens a Quick App four times per day

In terms of applications, the categories of news, ebooks, lifestyle, and tools have seen the greatest increase in usage levels and user stickiness.

“Proximity push” has also successfully directed traffic to offline stores. Specifically, it cites the example of Watsons, which worked together with 7 major smartphone manufacturers to use Quick App for marketing across 3,600 stores and achieved “more than 1 million visits and 460,000 new users within three days”.

The report also mentions extending Quick Apps into games and IOT—which is understandable, considering the hardware background of the consortium, but dubious considering the amorphousness of IOT as a category—and speculates on potential new applications brought about by 5G.

Notwithstanding these statistics, I am ultimately bearish on Quick Apps. Even if they are widely used as the entry point to these services, it is hard to assess how much of such usage is additive rather than substitutive (notably, the statistics above are MAU rather than DAU) and even harder to see how such value may be captured by the smartphone manufacturers. Once again, there is no “product-company fit” here, beyond the common goal of warding off Tencent.

Google Play Instant

As noted in the introduction, Google Play Instant ostensibly has not made much impact in the three years since its launch. My suspicion is that Google Play Instant is not widely adopted, though I was unable to find authoritative statistics on this point.

As far as I can tell, its value proposition is twofold:

Try before you download. Previously, users encountering an app in Google Play Store must make the binary decision of whether to download the app or not. Google Play Instant offers a third option: users can instantly load a smaller trial version of the app to experience it, before they are shown a prompt to download the full app.

Linking from other customer acquisition channels. Google Play Instant can also be triggered as a link from the usual customer acquisition channels (Google Search, social media, messaging etc.).

The major developers advertised by Google to have adopted Google Play Instant fall into two categories: (1) game developers (Candy Crush); or (2) information providers, such as NYTimes Crossword, Buzzfeed, and Skyscanner. Unlike Mini-Programs, Quick App, and Apple’s App Clip, Google Play Instant has thus far been a purely online experience. There is no O2O integration via QR code or NFC. It remains to be seen whether Google will lean into O2O, now that Apple has launched App Clip.

App Clip

Apple’s App Clip has only been recently announced and yet to be implemented. App Clip is supplemented by Apple’s suite of services and functionalities, most of which have counterparts in Google Play Instant and Mini-Programs:

App Clip is an extension of the native app on iOS and must go through Apple’s App Review.

App Clip allows for integration with “Sign in with Apple” and Apple Pay for identity and payment respectively.

App Clip can be launched using an “app clip code”, which encodes a URL and incorporates an NFC tag, so the code can be scanned by the camera or tapped on.

App Clip can also be launched from the Maps app , a suggestion from Siri Suggestions, or from a link shared in the Messages app.

Compared to Google Play Instant, App Clip envisions greater O2O integration, as evidenced by its range of “offline” access points like QR codes, NFC tags, and launching from Maps.

Compared to Mini-Programs in China, App Clip is “differentiated” by (1) being iOS-exclusive and (2) NFC support. I suspect QR codes seem to work just as well as NFC for most use cases (at least based on my firsthand observations in China) and as such, I have doubts that App Clip would be very competitive with the cross-platform Mini-Programs in China.

Nonetheless, NFC support speaks to Apple’s advantage deriving from integrating software and hardware. What are the O2O possibilities that might be unlocked using ultra-wideband or augmented reality if one day the U1 chip or the LiDAR scanner in the latest generation of iPhones and iPad Pro become as widespread as NFC?

The Future of Native Apps

For to every one who has will more be given, and he will have abundance; but from him who has not, even what he has will be taken away.

— Matthew 25:29, RSV.

There are many power law distributions in tech and app usage is probably one such distribution. If you look through your screen time allocation, a handful of apps—likely social networking ones—dominates most of your screen time.

The success of WeChat’s Mini-Program has illustrated that this power law distribution can effect be even more stark: many of the rarely-opened long-tail apps probably do not need to be native apps. This is largely an opportunity for tech companies that can leverage on a pre-existing, high-frequency relationship with consumers. However, the success of any particular attempt to implement mini-apps also crucially depends on its ability to achieve “product-company fit”.

Originally, in my Tweet, I framed Apple’s App Clip as an example of a Chinese tech innovation that is being exported to the rest of the world. But Apple’s App Clip is better understood as a defensive measure to forestall WeChat/Alipay-style cross-platform Mini-Programs. If, in the long run, many currently native apps are better implemented as mini-apps, it is better for Apple to hasten this transition and extend the App Store ‘toll-bridge’ business model accordingly.

Apple’s worst nightmare is exactly what is happening in China, where widely used apps like WeChat and Alipay operate cross-platform Mini-Programs that further empower themselves at the expense of iOS as a platform. (Unsurprisingly, there is great, unresolved tension between WeChat's Mini-Program and Apple's App Store rules, which I have explored here.) At the very least, Apple’s iOS-exclusive App Clip—if successfully implemented—could limit the expansion of cross-platform super-apps outside of China by redirecting the latent demand for mini-apps to the App Store instead.

In Tencent’s dispute with Apple over Mini-Programs’ compliance with App Store rules, one of Tencent’s argument is that the small file size of Mini-Programs actually complements the native app experience by lowering the barrier of experimentation. Mini-Programs are not sophisticated enough to pose a threat to native apps.

However, even if this is true now, it is also interesting to speculate how future technological trends might shift this calculus. Today, many native apps are already “merely” thin clients to access data stored on the cloud. Assuming sustaining innovation in the fields of 5G, mobile chips, and cloud computing, it is not difficult to imagine a future in which many more native apps apps might go the way of videos: to be streamed on demand rather than downloaded. In this future of mini-apps, at least in China, Tencent will be better positioned than Apple to capture the value created by mini-apps.

Smartphones have emerged as and likely will remain the most important computing platform for the foreseeable future. Mini-apps, as an emerging paradigm of mobile computing, is a space worth watching.

[1] I have only met one Chinese person who tried to minimize his WeChat usage by not using a smartphone at all. His daily driver consists of a feature phone and an iPad to connect to Wi-Fi. He also adopts obfuscatory measures and sets up his own ShadowSocks servers and is doing a PhD in computer science. So, all in all, not quite the average user.

[2] Dan Grover on this point: “WeChat's Mini-Programs, in trying to keep true to its founders vision, had initially stalwartly eschewed any way to find them other than scanning a QR code in the real world (even going so far as to literally block scanning one from a screenshot). This stance softened, as they added numerous new entry points and discovery surfaces throughout the app.”

[3] A point I neglected to mention in my previous post on Pinduoduo: Mini-Programs significantly reduces the friction from discovery to purchase, thus boosting conversion. Unsurprisingly, given Pinduoduo’s “social e-commerce” model, a much larger proportion of users access Pinduoduo via Mini-Programs, compared to other e-commerce platforms.

[4] Despite both being owned by Tencent, WeChat and QQ have a somewhat competitive relationship that is emblematic of Tencent’s “internal horse-racing management” style (赛马机制). A separate, equally interesting BigTechCo dynamic is other teams at Tencent trying to place their products in WeChat. Allegedly, the video-chat and payments tech in WeChat were all successfully forced in by teams outside of WXG.

[5] Personally, I used Tencent’s Android app store in China, which has the largest Android app store market share.

I would like to thank Dan Grover for his invaluable comments on earlier drafts of this essay. Any mistake is entirely my own.